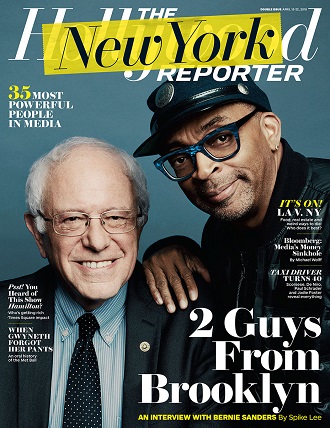

VAL 2016 | Det är inte var dag Bernie Sanders blir intervjuad av en anhängare och hamnar på omslaget till en rikstäckande tidskrift.

När regissören Spike Lee träffade senatorn för The Hollywood Reporter blev det inga hårdslående frågor. Sanders gick knappast därifrån svettig.

Det bästa man kan säga är att samtalet möjligtvis gav en lite tydligare bild av den självutnämnde ”demokratiska socialisten” Sanders åsikter i en rad ganska förutsägbara frågor.

Do you think that Mrs. Hillary Clinton has an advantage with her relationship with President Obama? I mean, what is your relationship with the president?

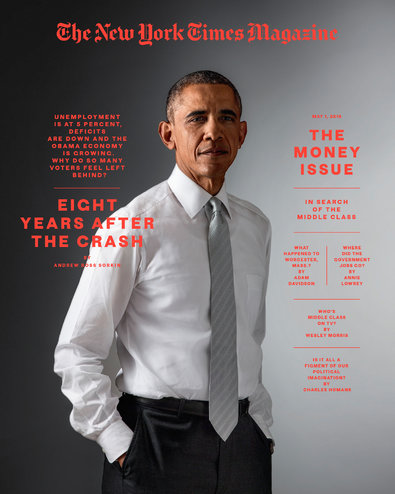

It’s a good relationship. But let me be very straight about this: This president will go down in history as one of the smartest presidents. Brilliant guy. And especially the more people hear from the Republicans, the smarter they think he is. (Laughter.) But he is also incredibly disciplined and focused. You’re around the media every single day, and you have the opportunity to say dumb things — he does it very, very rarely. He is very focused. He came to Vermont to campaign for me way back in 2006. I worked on his elections in 2008 and 2012 and just was in the Oval Office a couple of months ago. So we have a very positive and, I think, friendly relationship. Is he closer to Hillary Clinton? I suspect. She was his secretary of state for four years.

When did it hit you — I’m going to run for the United States of America? When did this happen?

I got to tell you there’s a funny story that every day 100 people brush their teeth and they look in the mirror and every one of them says, ”There is the next president of the United States.” That’s the definition of the U.S. Senate. Honestly, honestly, I was not one of those people.

It wasn’t you, huh?

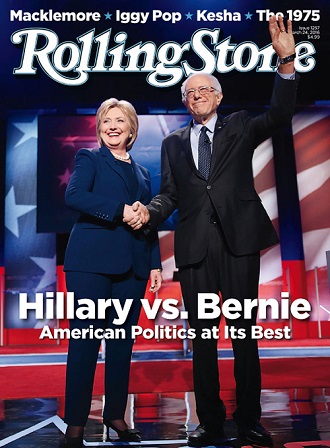

It wasn’t me. I love my state, very happy to be the senator. But this is what I concluded, Spike: With all due respect to Secretary Clinton and everybody else, it is too late for establishment politics and establishment economics. The problems facing this country now are so serious, are so deep, that the same-old, same-old ain’t going to do it. And what we need to do is create a political movement — what I call a political revolution — where millions of people come together.

A coalition, right?

Absolutely a coalition, based on the trade union movement, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the gay community movement and bringing people together to tell the billionaire class that they cannot have it all. People don’t appreciate how much power Wall Street has, corporate America, the corporate media. And we got to take ‘em on.

[…]

Trump. Have you seen the film A Face in the Crowd, directed by Elia Kazan? Do you see a correlation between Lonesome Rhodes [a character who rises to fame in the early days of TV], played by Andy Griffith, and Donald Trump?

He is an entertainer by and large. He did very well on television; he knows the media very, very well. Don’t underestimate him. And God knows who he is really, but we see what he personifies on TV every night. He knows how to manipulate the media very effectively, he knows how to do what he does with people. But let me just reassure you: Donald Trump is not going to become president of the United States. That I can say.

Would you agree that he is possibly the Frankenstein that the GOP has created? They got a monster on their hands and don’t know what to do with it.

There’s no question. The establishment Republicans are going nuts. And this could lead to a real dissolution of the Republican Party as we know it.

Who are the people who are voting for him? When a guy says I can stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue, shoot somebody — even saying that, knowing that 99 Americans die every day — and you’re going to shoot somebody and no one’s going to not vote for you? That’s insane to me.

Well, virtually every day he says something that’s crazier than the day before, right? So what can you say? But here is what I think is going on. I think that the establishment has underestimated the contempt and the frustration that the American people have, a segment of the American people have, with politics as usual.

With Washington, D.C., right?

Yeah, yeah. So when he says, ”Look, I’m not them,” they say, ”OK, that’s good enough for me.” You know? ”That’s all that I need.” And there is a lot of anger out there and a lot of reasons for the anger. One of the reasons for these 50-year-old, 60-year-old white guys voting for Trump is in many cases they are working longer hours for lower wages, they are seeing their jobs go to China, they are seeing their jobs go to Mexico. They are scared to death about the future of their kids, and they don’t see anybody doing anything about it. And Trump comes along and says, ”I got the solution, we’re going to scapegoat Mexicans and we’re going to build a wall a mile high.” People are angry, what do you do? You don’t get to the real issues as to why people are hurting, you scapegoat. You scapegoat blacks, Latinos, gays, anybody, Jews, Muslims, any minority out there, that’s what you do. That is nothing new. That’s what demagogues have always done, and that’s what Trump is doing. What we are trying to do in our campaign is bring people together to look at the real problems facing this country, which in my view is the greed of corporate America, of Wall Street, the grotesque level of income and wealth inequality. Let’s attack those issues. Let’s not scapegoat people.

Tidskriftsomslag: The Hollywood Reporter, den 15-22 april 2016.